Museums and exhibitions are some of the most important ways through which history is communicated to the public. Much like any other form of history they are influenced by factors, such as bias, selectivity and accuracy. They are also areas of contestation and debate, as they have a legitimisation effect. They can promote a certain narrative of the past to the public. However, people can also take different meanings from the same museum or experience based on cultural factors that affect them personally. This post aims to evaluate the role museums play in constructing public memory and how an individual's personal response to an exhibit can be related to this.

British Museum, London

The Construction of Memory

The role museums play in constructing public memory could perhaps be understood at first in terms of the Imagined Communities of Benedict Anderson. For some scholars, public history offers the images and symbols to hold diverse groups within a society together, Anderson himself stated a shared history- remembrance and forgetting in common- is a crucial instrument in the construction of a community. This view can be seen in the works of W. Lloyd Warner who analysed commemorative rituals in Yankee City and Pierre Nora's multivolume account of sites of memory (lieu de mémoire) in France. The view suggests that public history, including museums, is essentially consensual. In which a civic or national ideology is ultimately more important than those of cultural and economic differences (such as ethnicity and class). In this way museums help to create a sense of unity superior to any divisions. However, John Bodnar's Remaking America: Public Memory, Commemoration, and Patriotism in the Twentieth Century (1992) shows that there is a distinction between official memories (such as promoted by the government or a particular museum) and the vernacular memories that ordinary people have to sustain ties of family and local community. Exhibitions therefore should not just be understood as representations of a narrative the museum is trying to portray, but as places where individuals negotiate with their environment in the construction of their historical memory.

Individual responses to museums do not always correlate with the narrative it may be trying to show. Rowe, Werstch and Kosyaeva saw this in an exhibiton 'Unseen Treasures: Imperial Russia and the New World' put together by the American-Russian Cultural Cooperation Foundation. This was displayed in the Missouri History Museum, located in St Louis in the United States. The main narrative according to the museum itself is one that 'tells an adventurous story of heroism, romance and spiritual enlightenment through the lives of real people who shaped American-Russian relations in the 18th and 19th centuries'. It was organised into five sections, the first being on 'St Petersburg and the Imperial Court.' Rowe argues that this section shows the official narrative about the cultural grandeur and historical significance of European and Imperial Russia as seen by two views of the 19th century winter palace through a lithograph and an oil painting. These were also arranged with other physical objects from the Tsarist era. Both images concern the Arch of the General Staff Building, the painting showing Imperial soldiers marching through it.

Responses to the exhibition however did not conform with this narrative of Imperialist Russia, instead they tended to be connected more to personal memory. One respondent in the study stated 'It's the Winter Palace, and in 1985 I lived in St Petersburg for a summer with a friend of mine in her apartment, down the street here' another 'When I was a child growing up in St. Petersburg, the people would walk through the square everyday, and I took classes at the museum'. The importance of this is that it shows how museums act as points at which personal and public memory interact with each other. The narrative of the museum combines with the personal and emotional response of an individual who visits it.

To understand the role museums play in constructing memory, is therefore to understand how an individual's interaction with an exhibit shapes their response to it. Museums often act as intermediary spaces where personal and private memories come into contact with wider, collective memories. Rowe believes this dialogue can also be seen in the Missouri History Museum. One of the major goals for the Missouri Historical Society is to 'provide its diverse community with information about past human thought and activity, supplying critical context for analysis of persistent themes and significant issues in the present'. The museum is therefore supposed to be a link for the individual between the past and the present. Rowe sees this as a matter of accessibility, by connecting visitor's experiences of present-day St Louis to the past it creates a gateway to the wider general narrative of museum about the history of the area. It is an example of personal and public memories.

Contested Memory

As museums create different responses (emotional and in interpretation) they naturally become sites of controversy, where different narratives of the past negotiate. If a museum is supposed to be representative of the past then they act as discussion places for the validation of historical narratives. This can be seen in the 1990s over a dispute of an Enola Gay exhibit in the Smithsonian. The B-29 bomber was used the one used during the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. The dispute rose out of two conflicting narratives of the atomic bombings, according to to a 1993 planning document the exhibition's primary goal was 'to encourage visitors to make a thoughtful and balanced re-examination of the atomic bombings in the light of the political and military factors leading to the decision to use the bomb, the human suffering experienced by the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the long-term implications of the events of August 6 and 9, 1945'. This view therefore emphasis ed the suffering caused by the atomic bombings. Opposition of this narrative could be found among veteran groups and members of Congress, who argued that the exhibition was politically motivated and was trying to show the nuclear bombing of Japan was unnecessary.

By 30 September 1994 enough pressure was felt that parts of the exhibition were changed, the estimated casualties for a hypothetical conventional invasion of Japan were heavily altered. Previously, the exhibition stated that the United States would have only suffered 31,000 casualties in the first 30 days of fighting (less than the most estimates for bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki), now it stated American casualties could have ranged from 260,000 in the first phase to 1 million if they had to fight their way across the Japanese Islands. In this instance a museum was acting as a forum for debate over a historical event and controversy. By January 1995 the Enola Gay exhibit was cancelled by the Smithsonian Institute due to the continued controversy. The Smithsonian Secretary I. Michael Heyman went on to suggest that the institution should not hold such topical exhibitions again, halting projects on the Vietnam War and a NASM exhibition on air power.

The controversy of the Enola Gay exhibition can be viewed as a battle over public memory. As a museum mediates between the past and the public, it holds 'truth' value in the construction of the past. A museum can endorse a narrative, while at the same denouncing opposing narratives. It is therefore essentially a forum for the validity of a certain narrative within public memory of the past.

Smithsonian Institute Building

Conclusion

This post has suggested that museums acts a venue through which public and personal memory interlink and negotiate with each other. Museums can sometimes be created with a specific narrative in mind, but this does not mean an individual will interpret it in such a way. The variety of meanings an individual can take from the same exhibition means that they become sites of not only controversy, but also places where public memory is debated and contested.

Bibliography:

Image Credit goes to WikiCommons

British Museum, London

The Construction of Memory

The role museums play in constructing public memory could perhaps be understood at first in terms of the Imagined Communities of Benedict Anderson. For some scholars, public history offers the images and symbols to hold diverse groups within a society together, Anderson himself stated a shared history- remembrance and forgetting in common- is a crucial instrument in the construction of a community. This view can be seen in the works of W. Lloyd Warner who analysed commemorative rituals in Yankee City and Pierre Nora's multivolume account of sites of memory (lieu de mémoire) in France. The view suggests that public history, including museums, is essentially consensual. In which a civic or national ideology is ultimately more important than those of cultural and economic differences (such as ethnicity and class). In this way museums help to create a sense of unity superior to any divisions. However, John Bodnar's Remaking America: Public Memory, Commemoration, and Patriotism in the Twentieth Century (1992) shows that there is a distinction between official memories (such as promoted by the government or a particular museum) and the vernacular memories that ordinary people have to sustain ties of family and local community. Exhibitions therefore should not just be understood as representations of a narrative the museum is trying to portray, but as places where individuals negotiate with their environment in the construction of their historical memory.

Individual responses to museums do not always correlate with the narrative it may be trying to show. Rowe, Werstch and Kosyaeva saw this in an exhibiton 'Unseen Treasures: Imperial Russia and the New World' put together by the American-Russian Cultural Cooperation Foundation. This was displayed in the Missouri History Museum, located in St Louis in the United States. The main narrative according to the museum itself is one that 'tells an adventurous story of heroism, romance and spiritual enlightenment through the lives of real people who shaped American-Russian relations in the 18th and 19th centuries'. It was organised into five sections, the first being on 'St Petersburg and the Imperial Court.' Rowe argues that this section shows the official narrative about the cultural grandeur and historical significance of European and Imperial Russia as seen by two views of the 19th century winter palace through a lithograph and an oil painting. These were also arranged with other physical objects from the Tsarist era. Both images concern the Arch of the General Staff Building, the painting showing Imperial soldiers marching through it.

Responses to the exhibition however did not conform with this narrative of Imperialist Russia, instead they tended to be connected more to personal memory. One respondent in the study stated 'It's the Winter Palace, and in 1985 I lived in St Petersburg for a summer with a friend of mine in her apartment, down the street here' another 'When I was a child growing up in St. Petersburg, the people would walk through the square everyday, and I took classes at the museum'. The importance of this is that it shows how museums act as points at which personal and public memory interact with each other. The narrative of the museum combines with the personal and emotional response of an individual who visits it.

To understand the role museums play in constructing memory, is therefore to understand how an individual's interaction with an exhibit shapes their response to it. Museums often act as intermediary spaces where personal and private memories come into contact with wider, collective memories. Rowe believes this dialogue can also be seen in the Missouri History Museum. One of the major goals for the Missouri Historical Society is to 'provide its diverse community with information about past human thought and activity, supplying critical context for analysis of persistent themes and significant issues in the present'. The museum is therefore supposed to be a link for the individual between the past and the present. Rowe sees this as a matter of accessibility, by connecting visitor's experiences of present-day St Louis to the past it creates a gateway to the wider general narrative of museum about the history of the area. It is an example of personal and public memories.

Missouri History Museum, St Louis

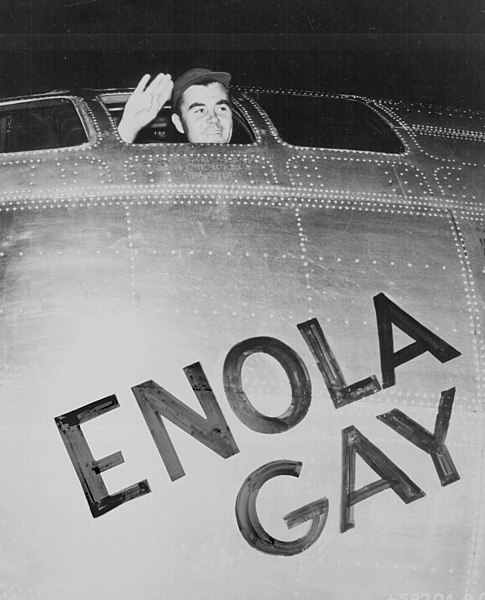

Paul Tibbets, pilot of the Enola Gay

Contested Memory

As museums create different responses (emotional and in interpretation) they naturally become sites of controversy, where different narratives of the past negotiate. If a museum is supposed to be representative of the past then they act as discussion places for the validation of historical narratives. This can be seen in the 1990s over a dispute of an Enola Gay exhibit in the Smithsonian. The B-29 bomber was used the one used during the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. The dispute rose out of two conflicting narratives of the atomic bombings, according to to a 1993 planning document the exhibition's primary goal was 'to encourage visitors to make a thoughtful and balanced re-examination of the atomic bombings in the light of the political and military factors leading to the decision to use the bomb, the human suffering experienced by the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the long-term implications of the events of August 6 and 9, 1945'. This view therefore emphasis ed the suffering caused by the atomic bombings. Opposition of this narrative could be found among veteran groups and members of Congress, who argued that the exhibition was politically motivated and was trying to show the nuclear bombing of Japan was unnecessary.

By 30 September 1994 enough pressure was felt that parts of the exhibition were changed, the estimated casualties for a hypothetical conventional invasion of Japan were heavily altered. Previously, the exhibition stated that the United States would have only suffered 31,000 casualties in the first 30 days of fighting (less than the most estimates for bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki), now it stated American casualties could have ranged from 260,000 in the first phase to 1 million if they had to fight their way across the Japanese Islands. In this instance a museum was acting as a forum for debate over a historical event and controversy. By January 1995 the Enola Gay exhibit was cancelled by the Smithsonian Institute due to the continued controversy. The Smithsonian Secretary I. Michael Heyman went on to suggest that the institution should not hold such topical exhibitions again, halting projects on the Vietnam War and a NASM exhibition on air power.

The controversy of the Enola Gay exhibition can be viewed as a battle over public memory. As a museum mediates between the past and the public, it holds 'truth' value in the construction of the past. A museum can endorse a narrative, while at the same denouncing opposing narratives. It is therefore essentially a forum for the validity of a certain narrative within public memory of the past.

Smithsonian Institute Building

Conclusion

This post has suggested that museums acts a venue through which public and personal memory interlink and negotiate with each other. Museums can sometimes be created with a specific narrative in mind, but this does not mean an individual will interpret it in such a way. The variety of meanings an individual can take from the same exhibition means that they become sites of not only controversy, but also places where public memory is debated and contested.

Bibliography:

Brown, Richard Harvey and Beth Davis-Brown. "The Making of memory: The Politics of Archives, Libraries and Museums in the Construction of National Consciousness." History of the Human Sciences 11, no. 4 (1998/11/01 1998): 17-32.

Glassberg, David. "Public History and the Study of Memory." The Public Historian 18, no. 2 (1996): 7-23.

Kohn, Richard H. "History and the Culture Wars: The Case of the Smithsonian Institution's Enola Gay Exhibition." Journal of American History 82, no. 3 (1995): 1036-63.

Rowe, Shawn M., James V. Wertsch, and Tatyana Y. Kosyaeva. "Linking Little Narratives to Big Ones: Narrative and Public Memory in History Museums." Culture & Psychology 8, no. 1 (2002/03/01 2002): 96-112.

'Smithsonian Substantially Alters Enola Gay Exhibit After Criticism' October 1 1994. http://www.nytimes.com/1994/10/01/us/smithsonian-substantially-alters-enola-gay-exhibit-after-criticism.html?mcubz=1 Accessed 07/09/2017.

Image Credit goes to WikiCommons

No comments:

Post a Comment