I have decided to start a new blog at https://philosophicalostrogoth.home.blog, as I am about to begin postgraduate studies. I will no longer update this site.

Liam's Look at History

History blog of a University of York student, including a range of articles and book reviews.

Friday, 19 July 2019

Tuesday, 18 June 2019

Dissertation Journal #5: Clusters and Conclusions

I have recently received my unconfirmed mark for my dissertation. I will therefore conclude my journal by discussing the final stages of my dissertation This will be done firstly be done by examining my thinking process for the final chapter and then by looking at potential directions for future research.

In my previous post, I discussed an anomaly surrounding the Roman Senate and how this helped me to think of an alternative model to the Gothic/Roman binary, which has often been used to understand social relations in Ostrogothic Italy. The final chapter of my dissertation aimed to take these ideas forward and apply them to the rest of the network. The first idea took forward from my previous chapter concerned the interaction between quantitative and qualitative techniques. In particular, how they are mutually beneficial to each other and the difficulty of using them in isolation. As mentioned earlier, my network was highly clustered and it was difficult to find a single 'rule' governing it. I therefore used Gephi's community detection features to isolate and identify small clusters, before examining the qualitative context from which they emerged from. The modularity algorithm used detected 96 communities in total.

I classified these communities under three main headings; 'administrative', 'diplomatic' and 'legal'. The intention of this was not to reduce all clusters into three types, but to provide a platform and structure for discussing the peculiarities of each individual instance. At this point, other ideas from the earlier in the dissertation came back to the forefront. Firstly, the overemphasis on ethnicity found in the current historiography. Secondly, the varying importance of alternative factors such as geographic location and particular titles. Finally, the role of 'practical reasons' or 'events' in causing connections. These ideas, with their emphasis on focusing on the microscopic level and the uniqueness of individual clusters, seemed to fit with the rest of the network.

Naturally, not every node or cluster followed these rules. A cluster surrounding two Goths, Duda and Tezutzat, protecting a Roman civilian called Petrus, reinforced rather than defied historiographic assumptions. A major surprise was that Praetorian Prefects, theoretically some of the most powerful individuals in Ostrogothic Italy, tended to have very few social connections. I suggested this was because they tended to move around quickly due to their wide remit over Italy. They struggled to build the more extensive networks of localised individuals, such as Urban Prefects. My emphasis in this chapter was on the need for a flexible understanding of social relations. One of my main issues with the Gothic/Roman binary is its simplicity and how historians (often, though not necessarily always) use it as a single answer for the social relations of an entire society.

A further issue addressed was the role of clustering in the network. Why was there no overarching rule to the network? Why were connections operating around separated and small communities? Following on from earlier ideas, I provided a number of explanations. Under the 'administrative' heading, I suggested clustering could be linked to Bjornlie's argument that Ostrogothic Italy had a decentralised and ad-hoc approach to governance. Individuals connecting around bureaucratic operations were chosen because they were in the right location at the right time and because they had the title necessary for them to carry out a task. There was not a central 'pool' of officials around one area, individuals were spread out across Italy. However, I was hesitant to use my data to support Bjornlie's further suggestion a more decentralised approach to governance was indicative of decline. Firstly, due to the lack of a comparative data sample prior to Ostrogothic rule in Italy. Secondly, because a decentralised approach may have been a conscious and proactive decision to make the administration more suitable for the early sixth-century, rather than a simple fall from earlier Roman standards. In the context of 'legal' clusters, this explanation for clustering was again relevant. Lafferty has argued legal cases were dealt with by a provincial governor, irrespective of an individuals' ethnicity. Therefore, clusters surrounding law were also linked to a 'ad-hoc' decentralised approach. Finally, I also made some indications that the temporariness of connections may account for some of the clustering. If individuals did not 'socialise' or 'connect' outside of events or government orders, they would not have had any opportunities to develop more complete networks.

In my previous post, I discussed an anomaly surrounding the Roman Senate and how this helped me to think of an alternative model to the Gothic/Roman binary, which has often been used to understand social relations in Ostrogothic Italy. The final chapter of my dissertation aimed to take these ideas forward and apply them to the rest of the network. The first idea took forward from my previous chapter concerned the interaction between quantitative and qualitative techniques. In particular, how they are mutually beneficial to each other and the difficulty of using them in isolation. As mentioned earlier, my network was highly clustered and it was difficult to find a single 'rule' governing it. I therefore used Gephi's community detection features to isolate and identify small clusters, before examining the qualitative context from which they emerged from. The modularity algorithm used detected 96 communities in total.

I classified these communities under three main headings; 'administrative', 'diplomatic' and 'legal'. The intention of this was not to reduce all clusters into three types, but to provide a platform and structure for discussing the peculiarities of each individual instance. At this point, other ideas from the earlier in the dissertation came back to the forefront. Firstly, the overemphasis on ethnicity found in the current historiography. Secondly, the varying importance of alternative factors such as geographic location and particular titles. Finally, the role of 'practical reasons' or 'events' in causing connections. These ideas, with their emphasis on focusing on the microscopic level and the uniqueness of individual clusters, seemed to fit with the rest of the network.

Graph showing size of clusters in the network.

Naturally, not every node or cluster followed these rules. A cluster surrounding two Goths, Duda and Tezutzat, protecting a Roman civilian called Petrus, reinforced rather than defied historiographic assumptions. A major surprise was that Praetorian Prefects, theoretically some of the most powerful individuals in Ostrogothic Italy, tended to have very few social connections. I suggested this was because they tended to move around quickly due to their wide remit over Italy. They struggled to build the more extensive networks of localised individuals, such as Urban Prefects. My emphasis in this chapter was on the need for a flexible understanding of social relations. One of my main issues with the Gothic/Roman binary is its simplicity and how historians (often, though not necessarily always) use it as a single answer for the social relations of an entire society.

A further issue addressed was the role of clustering in the network. Why was there no overarching rule to the network? Why were connections operating around separated and small communities? Following on from earlier ideas, I provided a number of explanations. Under the 'administrative' heading, I suggested clustering could be linked to Bjornlie's argument that Ostrogothic Italy had a decentralised and ad-hoc approach to governance. Individuals connecting around bureaucratic operations were chosen because they were in the right location at the right time and because they had the title necessary for them to carry out a task. There was not a central 'pool' of officials around one area, individuals were spread out across Italy. However, I was hesitant to use my data to support Bjornlie's further suggestion a more decentralised approach to governance was indicative of decline. Firstly, due to the lack of a comparative data sample prior to Ostrogothic rule in Italy. Secondly, because a decentralised approach may have been a conscious and proactive decision to make the administration more suitable for the early sixth-century, rather than a simple fall from earlier Roman standards. In the context of 'legal' clusters, this explanation for clustering was again relevant. Lafferty has argued legal cases were dealt with by a provincial governor, irrespective of an individuals' ethnicity. Therefore, clusters surrounding law were also linked to a 'ad-hoc' decentralised approach. Finally, I also made some indications that the temporariness of connections may account for some of the clustering. If individuals did not 'socialise' or 'connect' outside of events or government orders, they would not have had any opportunities to develop more complete networks.

Having outlined some of my conclusions during the latter stages of my dissertation, I will now discuss some of the potential directions for future research. The first would be to simply use more varied and extensive evidence to further test my findings. My dissertation covered the first books of Cassiodorus' Variae, which are all from the reign of Theoderic the Great. Using the latter books and other sources, like Procopius' History of the Wars, would allow an analysis that focuses more heavily on any potential changes over time. Dynamic Network Analysis (DNA) rather than standard SNA would be more suitable for this task, as it represents change better than the static visualisations and metrics used in my dissertation. I also think consulting other types of sources would be useful. Even Boethius' Consolation of Philosophy contains incidental references to social connections, considering other genres like this could be useful. They could offer further insight due to their differences to the government-oriented Variae, in particular regarding connections outside of 'practical' concerns or events.

Aside from confirming or refuting my findings, I believe my ideas could be took into another direction. Network analysis could be used to examine a number of interdisciplinary and philosophical issues. Many of the findings in my dissertation indicate it would be wrong to view Ostrogothic social relations as 'simple', instead they seem to match with the concept of 'complexity' found in the natural and social sciences. I believe there is room for interdisciplinary dialogue here, particularly regarding the ontological nature of relations. By 'borrowing' Network Analysis for a historical study, I have portrayed relations as polyadic. This would seem to be at odds with the binarism prevalent in the current historiography on Goths/Romans. Several interesting questions could be raised here. How far is my representation of relations an accurate reflection of reality or alternatively a result of using a technique originally developed in other disciplines? Likewise, if Late Antique philosophers conceived of relations generally in a non-polyadic fashion, would there be a problematic contradiction with my findings? Finally, there is also a need to consider the presumptions historians are carrying when analysing relations. By suggesting Goths/Romans were separate, yet harmoniously working together, are we not be presuming the subjects of a relation have greater ontological priority than the relation itself? I believe these theoretical issues could be addressed by using Network Analysis as a 'gateway' for relevant discussion.

Having concluded my dissertation, I believe there is room to develop some of my ideas. By keeping a journal, I have hoped to keep a record of the processes involved in writing my dissertation. Firstly, for my own sake, in case I return to these ideas in the future. Secondly, because I genuinely believe some of the ideas contained in my dissertation could be quite important if developed further. Overall, keeping a journal has been an enjoyable process and I hope my entries have given some insight into my thinking.

Aside from confirming or refuting my findings, I believe my ideas could be took into another direction. Network analysis could be used to examine a number of interdisciplinary and philosophical issues. Many of the findings in my dissertation indicate it would be wrong to view Ostrogothic social relations as 'simple', instead they seem to match with the concept of 'complexity' found in the natural and social sciences. I believe there is room for interdisciplinary dialogue here, particularly regarding the ontological nature of relations. By 'borrowing' Network Analysis for a historical study, I have portrayed relations as polyadic. This would seem to be at odds with the binarism prevalent in the current historiography on Goths/Romans. Several interesting questions could be raised here. How far is my representation of relations an accurate reflection of reality or alternatively a result of using a technique originally developed in other disciplines? Likewise, if Late Antique philosophers conceived of relations generally in a non-polyadic fashion, would there be a problematic contradiction with my findings? Finally, there is also a need to consider the presumptions historians are carrying when analysing relations. By suggesting Goths/Romans were separate, yet harmoniously working together, are we not be presuming the subjects of a relation have greater ontological priority than the relation itself? I believe these theoretical issues could be addressed by using Network Analysis as a 'gateway' for relevant discussion.

Having concluded my dissertation, I believe there is room to develop some of my ideas. By keeping a journal, I have hoped to keep a record of the processes involved in writing my dissertation. Firstly, for my own sake, in case I return to these ideas in the future. Secondly, because I genuinely believe some of the ideas contained in my dissertation could be quite important if developed further. Overall, keeping a journal has been an enjoyable process and I hope my entries have given some insight into my thinking.

Primary Sources:

Boethius, De Consolatione Philosophiae in The Consolation of Philosophy translated

by Victor Watts. London: Penguin, 1969.

Cassiodorus,

Variae in The Letters of

Cassiodorus: Being A Condensed Translation Of The Variae Epistolae Of

Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator translated by Thomas Hodgkin. London:

Henry Frowde, 1886.

Procopius,

History of the Wars in Procopius translated by William H. Dewey in 7 volumes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press, 1914-1940.

Secondary Sources:

Bjornlie,

Shane. "Governmental Administration." In A Companion to Ostrogothic Italy, edited by

Jonathan J. Arnold, Shane Bjornlie and Kristina Sessa, 47-72. Leiden: Brill,

2016.

Carley,

Kathleen M. "Dynamic Network Analysis." In Dynamic Social Network Modeling and Analysis: Workshop Summary

and Papers, edited by Ronald Breiger, Kathleen M. Carley and Philippa

Pattison, 133-45. Washington: National Academies Press, 2003.

Lafferty,

Sean D.W. Law and Society in the Age of

Theoderic: A Study of the Edictum Theoderici. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013.

-

Thursday, 28 March 2019

Dissertation Journal #4: Explaining an Anomaly and Methodological Issues

Since my last post, I have completed the first draft of my dissertation. In this entry, I hope to raise some of the methodological issues that I encountered during this process. This will be done by focusing on an anomaly in my data that centered around the Roman Senate and the problems I faced while trying to explain it through Social Network Analysis (SNA).

I will firstly highlight the characteristics that separated the anomaly from the norms of the network. Firstly, it was a relatively dense and highly-connected area of the network. The findings of my first chapter suggested that Ostrogothic Italy on the whole tended to be a relatively divided society. However, the anomalous group of 39 nodes challenged this. The betweenness centrality for this cluster was 8.946078412, whereas for the entire network it was only 1.164930545 (Theoderic the Great was excluded from these calculations as he connects to everyone). A higher score on this metric indicates the extent to which a node mediates relations, so it became clear this group of 39 nodes had unusually high levels of interconnectivity. The second defining characteristic of the anomaly was that it had a higher percentage of nodes with the label 'Roman'. Non-Romans were only 10.24% of the cluster, in contrast to forming 51.9% of the entire network.

The first questions needing to be addressed were simple. Was this anomaly contradicting the points I developed earlier in the dissertation about ethnicity not being important in Ostrogothic social relations? Furthermore, could the anomaly instead be characterised as an 'ethnic' enclave for Romans? The answers were not necessarily simple. While being numerically inferior, 'Gothic' and 'Unknown' nodes still tended to score equally if not higher than 'Roman' nodes on most metrics. In other words, this anomaly was an intensification of the patterns established in my first chapter. There were more Romans, but this did not necessarily translate to them being more important or separate from Goths in terms of connections.

By examining other factors that may have influenced the creation of the anomaly, I hoped to more adequately address this group of nodes. I firstly assessed if holding a certain 'title' was important. Firstly, I noticed the anomaly had a high concentration of individuals who were Viri Illustres. By Late Antiquity, this was the only title that allowed admission to the Roman Senate. It is worth noting here that during this period an individual could very well hold senatorial status through a different title, but only this one could allow participation in the Senate as a political institution. However, aside from this, there were also some odd titles in the data, such as Arch-Physician and Pantomimist. In this way, it was clear that participation in the Senate was important, but at the same time more answers were needed. An analysis of individuals' zones of activity yielded similar results. Rome was particularly prominent as a location for individuals in this group, which again reinforced my conviction that the Senate was playing an important role. With this mind, I suggested the higher rates of interconnectivity in the anomaly could potentially be linked to the the independence the Senate still held as an institution, with it being less dependent on the patronage of Theoderic. Meanwhile, the changes in the ratio of Goths to Romans were a result of the Senate's relatively small size in comparison to the rest of the Ostrogothic bureaucracy. It was harder for everyone, not just Goths, to be a part of the Senate. Despite all of this, there were still too many nodes within the anomaly that could not be entirely explained by the Roman Senate and so I was required to consider additional factors.

A screenshot of part of the anomaly, with Romans in red and the other nodes representing nodes with non-Roman labels.

It was at this point, I began to consider a number of methodological issues. The first was whether my application of SNA to the letters of Cassiodorus was giving undue importance to this anomaly. This came to mind because the group contained a particularly prominent clique originating from only 2 of the 229 letters studied. A clique is a set of nodes where every possible connection is made. The connections in this clique occurred twice, which was highly unusual, as individuals in the network tended to connect only once and never again. However, there were only 9 nodes in this clique and 30 other ones with the aforementioned anomalous traits still remained. Further answers were needed.

Having exhausted what the data was telling me about the anomaly, I decided to see if I was missing something by using quantitative rather than qualitative techniques. In particular, I wanted to examine the contexts in which individual connections were taking place. By doing this, I noticed that individuals were primarily meeting as a response to 'events' or for practical reasons, such as an administrative order (e.g collecting taxes, etc). This allowed me to develop a model for understanding the anomaly which relied on both SNA and readings of my source. Factors, such as 'titles' or 'zones of activity' were indeed important in the creation of the anomaly. However, social relations are not necessarily predictable. For example, we cannot presume the pantomimist Helladius would have not had everyday access to the powerful Urban Prefect of Rome. Yet, they connected anyway due to disturbances at the circus. It was on this basis, I suggested that while certain factors can influence the likelihood of a connection (in this case, they both shared Rome), they do not in themselves create it- there needs to be a reason for a relation. In this way, the quantitative data was useful for identifying that being part of a Roman Senate was an important factor for the anomaly, whereas looking at the sources allowed a more fuller explanation for any peculiarities. The Roman Senate was not rigid, it encountered people outside of its own ranks due to daily practical activities, and to expect a 'pure' undifferentiated set of nodes within the anomaly would have missed the point. It would have portrayed social relations as hierarchical, predictable and overly simplistic.

Following this necessary interaction of quantitative and qualitative techniques, I thought it was necessary to raise some of the methodological implications. For example, are statistics better at explaining some problems better than others? Should the historian use SNA and traditional document-reading alongside each other? Based on my findings, I suggested it would be wrong to take the view we need to choose one or the other. In fact, both methodologies can be mutually beneficial to each other. SNA can be helpful for complicating structures that may have been taken for granted in the historiography (in this instance, the role of ethnicity), while also allowing us to assess the importance of other factors in social relations. Whereas, qualitative techniques allow a more microscopic look at instances which defy our expectations. I took many of the ideas developed when analysing this anomaly into my final chapter, which looked at the variety of smaller clusters that made up the rest of the network. Hopefully, this post offers insight into my thought processes on the methodological issues I encountered while writing my dissertation.

Having exhausted what the data was telling me about the anomaly, I decided to see if I was missing something by using quantitative rather than qualitative techniques. In particular, I wanted to examine the contexts in which individual connections were taking place. By doing this, I noticed that individuals were primarily meeting as a response to 'events' or for practical reasons, such as an administrative order (e.g collecting taxes, etc). This allowed me to develop a model for understanding the anomaly which relied on both SNA and readings of my source. Factors, such as 'titles' or 'zones of activity' were indeed important in the creation of the anomaly. However, social relations are not necessarily predictable. For example, we cannot presume the pantomimist Helladius would have not had everyday access to the powerful Urban Prefect of Rome. Yet, they connected anyway due to disturbances at the circus. It was on this basis, I suggested that while certain factors can influence the likelihood of a connection (in this case, they both shared Rome), they do not in themselves create it- there needs to be a reason for a relation. In this way, the quantitative data was useful for identifying that being part of a Roman Senate was an important factor for the anomaly, whereas looking at the sources allowed a more fuller explanation for any peculiarities. The Roman Senate was not rigid, it encountered people outside of its own ranks due to daily practical activities, and to expect a 'pure' undifferentiated set of nodes within the anomaly would have missed the point. It would have portrayed social relations as hierarchical, predictable and overly simplistic.

Following this necessary interaction of quantitative and qualitative techniques, I thought it was necessary to raise some of the methodological implications. For example, are statistics better at explaining some problems better than others? Should the historian use SNA and traditional document-reading alongside each other? Based on my findings, I suggested it would be wrong to take the view we need to choose one or the other. In fact, both methodologies can be mutually beneficial to each other. SNA can be helpful for complicating structures that may have been taken for granted in the historiography (in this instance, the role of ethnicity), while also allowing us to assess the importance of other factors in social relations. Whereas, qualitative techniques allow a more microscopic look at instances which defy our expectations. I took many of the ideas developed when analysing this anomaly into my final chapter, which looked at the variety of smaller clusters that made up the rest of the network. Hopefully, this post offers insight into my thought processes on the methodological issues I encountered while writing my dissertation.

Secondary Sources:

Heather, Peter. "Senators and Senates." In The Cambridge Ancient History: Volume 13: The Late Empire, AD 337–425, edited by Averil Cameron and Peter Garnsey, 184-210. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Radtki, Christine. "The Senate at Rome in Ostrogothic Italy." In A Companion to Ostrogothic Italy, edited by Jonathan J. Arnold, Shane Bjornlie and Kristina Sessa, 121-46. Leiden: Brill, 2016.

Scott, John. Social Network Analysis: A Handbook. 2017 ed. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, 1991.

Wednesday, 23 January 2019

Dissertation Journal #3: Applying Metrics and Analysing the Network

In my last post, I discussed the processes involved in constructing a social network. This entry will build on this by looking at how I analysed the network. I will firstly introduce some of the methods used to do this, before discussing what they reveal about social relations in Ostrogothic Italy. Most of what will be discussed here ended up forming the basis of my the first chapter of my dissertation and so this entry will give some insight into how I came to my conclusions.

The software used for analysing the network was Gephi, which aids Social Network Analysis (SNA) in two ways. Firstly, by visualising the network, allowing the researcher to identify patterns. An image of part of my network, as visualised in Gephi, can be seen below. To aid my investigations for the first chapter, I colour-coded the different nodes based on their 'ethnic' label. Red nodes were Roman, whereas purple ones were Gothic. Likewise, blue nodes represented individuals that are classified as 'Unknown' and green ones represent individuals classified under 'Other', such as Visigoths or Franks. In this image, lines between people mean they are connected at least once. A visual representation such as this was useful, as it allowed me to analyse the network on a smaller scale. For example, by looking at a representation, I was able to identify a clique based around the Roman Senate going against the norm of the network established by metrical means.

Part of the network, colour-coded for my analysis.

I will now move on to the aforementioned ability to use metrics in Gephi. Social Network Analysis often involves using a range of formula which help the researcher to identify patterns. These can be calculated for the network as a whole. For example, global density helps to identify how complete or connected the entirety of the network is. This is calculated by expressing the number of lines in the network as a proportion of the maximum number of lines. It was therefore useful for identifying the divided nature of my network. The average clustering coefficient is another metric calculated globally and is used to understand the tendency of individuals to form into clusters within the network.

There are also a number of metrics that assign scores to individuals, rather than on a global-level. Closeness centrality calculates the shortest route through which a node tends to be connected to other nodes in the network, whether this is directly or through an intermediary. Eigenvector centrality is similar to this, except it is based on how far a node is connected to the most central nodes. Metrics such as these can be useful for finding out who the most important people in the network are. However, they are also useful for finding out averages for different node types. For example, it was possible to work out that Goths and Romans were generally equal in importance in terms of their place in the network. As I used a range of technical vocabulary, like the ones described here, throughout the first chapter, I decided to restrict definitions to the appendices of my dissertation. This is to prevent detraction from my argument in the main body of the text.

I will now discuss some of my findings from applying these forms of analyses for the first chapter of my dissertation. The first and most significant finding was that connections between individuals did not tend to be made in the context of ethnicity. Most modern scholarship accepts that ethnicity does not have an unchanging biological basis. However, historians have still tended to emphasise the importance of ethnicity, even it its ideological or constructed form, when understanding Ostrogothic society. My research has questioned this assumption in multiple ways. Firstly, as mentioned, average centrality scores for individuals in the network tended to be the same for Goths and Romans. They were unable to be distinguished in this way. Secondly, based on a visual analysis of my network I noticed that while nodes did tend to coalesce into groups, there was no basis to use ethnicity as an explanation for this. Nodes of different ethnic labels tended to connect with each other more often than not. The final statistic that supported this point were the percentages at which Goths and Romans connected with other 'ethnic' labels. Based on a 20% sample of all Goths in the network, I found out that Goths tended to connect more with Romans rather than their fellow Goths.

The second finding of my research was that the military/civilian divide that has characterised discussion around Ostrogothic Italy is not supported by a statistical analysis. Goths have often been seen as 'soldiers' and Romans as 'civilians'. Nearly every single title within my study was either civilian or straggled the apparent divide. For example, many titles such as Dukes, had civilian and military duties. However, some titles did seem to be associated with particular 'ethnic' labels. For example the 17 Sajones in the data were all Gothic. Sajones were experienced soldiers, who usually held judicial roles. However, this was not a suitable foundation to argue for a military/civilian divide, the holders of this title still tended to associate with Romans more than Goth, in spite of being Gothic themselves.

This entry has established the different methodologies I used to carry out an analysis of social relations in Ostrogothic Italy and pointed towards how I came to the conclusions established in the first chapter of my dissertation. After dismissing the traditional ethnic interpretations, the rest of the analyses of my network will focus on establishing a new model for understanding society in early sixth-century Italy.

Secondary Sources:

The software used for analysing the network was Gephi, which aids Social Network Analysis (SNA) in two ways. Firstly, by visualising the network, allowing the researcher to identify patterns. An image of part of my network, as visualised in Gephi, can be seen below. To aid my investigations for the first chapter, I colour-coded the different nodes based on their 'ethnic' label. Red nodes were Roman, whereas purple ones were Gothic. Likewise, blue nodes represented individuals that are classified as 'Unknown' and green ones represent individuals classified under 'Other', such as Visigoths or Franks. In this image, lines between people mean they are connected at least once. A visual representation such as this was useful, as it allowed me to analyse the network on a smaller scale. For example, by looking at a representation, I was able to identify a clique based around the Roman Senate going against the norm of the network established by metrical means.

Part of the network, colour-coded for my analysis.

I will now move on to the aforementioned ability to use metrics in Gephi. Social Network Analysis often involves using a range of formula which help the researcher to identify patterns. These can be calculated for the network as a whole. For example, global density helps to identify how complete or connected the entirety of the network is. This is calculated by expressing the number of lines in the network as a proportion of the maximum number of lines. It was therefore useful for identifying the divided nature of my network. The average clustering coefficient is another metric calculated globally and is used to understand the tendency of individuals to form into clusters within the network.

There are also a number of metrics that assign scores to individuals, rather than on a global-level. Closeness centrality calculates the shortest route through which a node tends to be connected to other nodes in the network, whether this is directly or through an intermediary. Eigenvector centrality is similar to this, except it is based on how far a node is connected to the most central nodes. Metrics such as these can be useful for finding out who the most important people in the network are. However, they are also useful for finding out averages for different node types. For example, it was possible to work out that Goths and Romans were generally equal in importance in terms of their place in the network. As I used a range of technical vocabulary, like the ones described here, throughout the first chapter, I decided to restrict definitions to the appendices of my dissertation. This is to prevent detraction from my argument in the main body of the text.

I will now discuss some of my findings from applying these forms of analyses for the first chapter of my dissertation. The first and most significant finding was that connections between individuals did not tend to be made in the context of ethnicity. Most modern scholarship accepts that ethnicity does not have an unchanging biological basis. However, historians have still tended to emphasise the importance of ethnicity, even it its ideological or constructed form, when understanding Ostrogothic society. My research has questioned this assumption in multiple ways. Firstly, as mentioned, average centrality scores for individuals in the network tended to be the same for Goths and Romans. They were unable to be distinguished in this way. Secondly, based on a visual analysis of my network I noticed that while nodes did tend to coalesce into groups, there was no basis to use ethnicity as an explanation for this. Nodes of different ethnic labels tended to connect with each other more often than not. The final statistic that supported this point were the percentages at which Goths and Romans connected with other 'ethnic' labels. Based on a 20% sample of all Goths in the network, I found out that Goths tended to connect more with Romans rather than their fellow Goths.

The second finding of my research was that the military/civilian divide that has characterised discussion around Ostrogothic Italy is not supported by a statistical analysis. Goths have often been seen as 'soldiers' and Romans as 'civilians'. Nearly every single title within my study was either civilian or straggled the apparent divide. For example, many titles such as Dukes, had civilian and military duties. However, some titles did seem to be associated with particular 'ethnic' labels. For example the 17 Sajones in the data were all Gothic. Sajones were experienced soldiers, who usually held judicial roles. However, this was not a suitable foundation to argue for a military/civilian divide, the holders of this title still tended to associate with Romans more than Goth, in spite of being Gothic themselves.

This entry has established the different methodologies I used to carry out an analysis of social relations in Ostrogothic Italy and pointed towards how I came to the conclusions established in the first chapter of my dissertation. After dismissing the traditional ethnic interpretations, the rest of the analyses of my network will focus on establishing a new model for understanding society in early sixth-century Italy.

Secondary Sources:

Amory, Patrick. People and Identity in Ostrogothic Italy, 489-554. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Heather, Peter. "Merely an Ideology? Gothic Identity in Ostrogothic Italy." In The Ostrogoths from the Migration Period to the Sixth Century: An Ethnographic Perspective, edited by Sam Barnish and Federico Marazzi, 31-80. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press, 2007.

Knoke, David and Song Yang. Social Network Analysis. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, 2000.

Scott, John. Social Network Analysis: A Handbook. 2017 ed. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, 1991.

Saturday, 3 November 2018

Dissertation Journal #2: Completing the Network and Resolving Problems

Over the summer and since my previous post, I have completed entering the data necessary to create a social network based on Cassiodorus' Variae. In this entry, I not only hope to show the process by which this was carried out, but also show the problems that can arise in a research project of this size and nature and how they can be resolved or at least circumvented. I will do this by firstly examining the process for collecting the data for the nodes or individuals within the network and then move on to look at the wedges or connections.

The data for this project was collected through a reading of the first five books of Cassiodorus' Variae and then was entered into Microsoft Excel. The first Excel sheet for my database was for the 'nodes'. This mainly consisted of the characteristics of the individuals in the network which were collected under a series of labels; their name, the origin of their name or ethnicity, gender, occupation and finally their location. An additional column was reserved for a range of additional notes relevant to creating the network, such as my reasoning for making certain decisions. It is clear that the labels I used for collecting the data were based on structures (such as class and ethnicity) that have had prominence in recent debates on Ostrogothic Italy. While this may indeed have neglected other aspects of the text, I believe my choices are justified as one of the aims of my project was to ask whether recent historiography stands up to scrutiny when the Variae are analysed quantitatively instead of qualitatively. Likewise, I believe a technique like Social Network Analysis, as it examines connections between people, can be used to examine the usefulness of these categories.

However, a specific problem did arise when trying to enter the geographic location of individuals within the network. When I initially started my project I expected I would able to pinpoint the 'home' location of an individual, in essence where they spend most of their time. However, this rarely came up while reading the Variae and therefore left a column of almost entirely 'unknowns'. For example, I was able to work out that a certain Florianus and Annas were both involved in a dispute over a farm at Mazennes, but the text provided no clue to whether they were actually from this area. A second and more serious problem was that by focusing on the 'home' location of an individual, I was in danger of ignoring what the source was telling me with regards to the geographic mobility of certain people within the Ostrogothic Kingdom, as individuals in the Variae were appearing in multiple places. My dissertation supervisor suggested that a solution to these problems could be to change my initial label of 'location' for the column to a more general one of 'zones of activity'. I believe this solution, of entering multiple locations, helped to avoid losing some of the nuance of the Variae. In one of the most extreme instances, the Praetorian Prefect Faustus, could be found in 14 different locations, ranging from the Cottian Alps to Campania, and instances such as these could not be simply ignored.

Entering the data for the other labels in the nodes table was generally easier, however a number of issues did arise when deciding the ethnicity of a particular person, especially whether they should be termed Roman or Gothic. My main sources for the decision part of this category were two reference works, The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire. and the prosopography found within Amory's People and Identity in Ostrogothic Italy, 489-554. As early medieval scholarship has moved to a more fluid definition of ethnicity, these works had a number of criteria for determining whether a person was Roman or Gothic, aside from the linguistic origin of their name. This, of course, meant there were certain scenarios where the ethnicity of a person was not clear. For example, neither Amory or Martindale could decide the best term to describe an individual called Starcedus. Furthermore, an individual named Colossaeus may have initially appeared to have a Roman name, but the Variae themselves state that he is Gothic (Var. III 23). In some instances there were people who were neither Gothic or Roman, therefore I often used the particular context of an individual to make a decision. For example, Clovis, as King of the Franks, was termed 'Frankish'.

Further complications were the result of my translation of the Variae, the nineteenth-century edition by Thomas Hodgkin. As the best version of the Variae available in English, it is a pivotal work for my dissertation, especially for the purposes of collecting data. This is due to the fact that it contains all the letters from Latin edition, even if in an abridged format. However, it is not perfect, Hodgkin has a tendency to be inconsistent in his use of names and titles. The Assuin mentioned in Book 1, is the same as the Ossuin in Books 3 and 4, however Hodgkin uses both versions of the name without stating it is the same person. In such confusing instances, my reference works were valuable in establishing such connections.

Concurrently to entering the data for the nodes table, I had to compile an incidence matrix to create the wedges or connections within the social network. As shown above, this involved entering a '1' in a column when an individual was a participant in a letter or a '0' if they were not. The letters of the Variae were represented in the top row by the alphabet. A matrix such as this was the easiest way to collect the data, as it accommodated my approach of reading through the Variae one by one. However, it was difficult to transfer this part of the database over to Gephi, the software I am using for the metrics and visualisation of the network. I was therefore required to create a source-target table (as shown below) to do this. This simply involved typing the two IDs (their numerical reference) of the participants within the connection and attributing to them a 'weight'. A higher 'weight' between two people indicates that they are more closely connected, for my purposes this was how often they were mentioned together within Cassiodorus' letters, which was often only once.

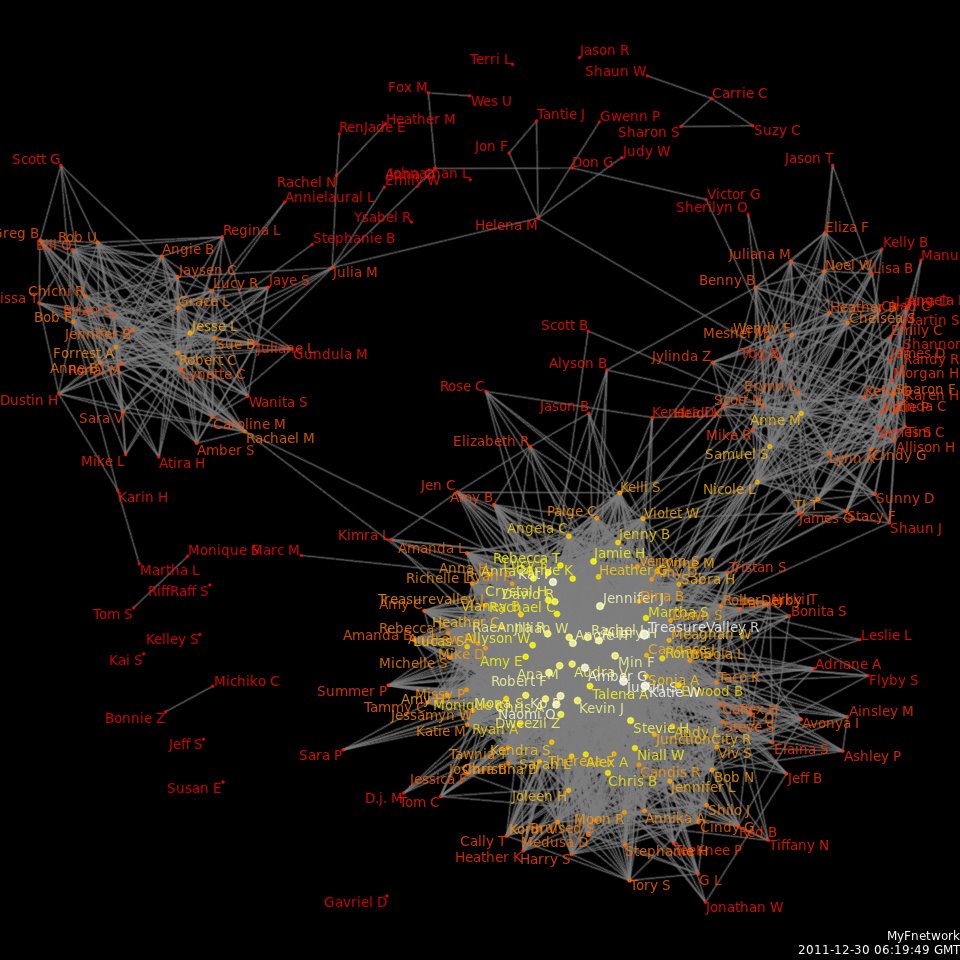

Visualisation of my network in Gephi.

The creating of the source-target table formed the final part of my data collection process. After this I transferred it all over to Gephi and ran an algorithm, which helped to create the visualisation of the network also shown above. I immediately detected, unsurprisingly, that Theodoric the Great was at the centre of the network due to his participation in all the letters of the first five books of the Variae. However, I also noticed a number of cliques or groups within the network, particularly around those individuals who were based around Rome or were members of the senate. Argolicus, the Urban Prefect of the city is the most connected individual in the network aside from Theodoric. As my dissertation work continues, I will continue to analyse these different intricacies of the network, most notably by using the metric tools available within Gephi.

Primary Sources:

The data for this project was collected through a reading of the first five books of Cassiodorus' Variae and then was entered into Microsoft Excel. The first Excel sheet for my database was for the 'nodes'. This mainly consisted of the characteristics of the individuals in the network which were collected under a series of labels; their name, the origin of their name or ethnicity, gender, occupation and finally their location. An additional column was reserved for a range of additional notes relevant to creating the network, such as my reasoning for making certain decisions. It is clear that the labels I used for collecting the data were based on structures (such as class and ethnicity) that have had prominence in recent debates on Ostrogothic Italy. While this may indeed have neglected other aspects of the text, I believe my choices are justified as one of the aims of my project was to ask whether recent historiography stands up to scrutiny when the Variae are analysed quantitatively instead of qualitatively. Likewise, I believe a technique like Social Network Analysis, as it examines connections between people, can be used to examine the usefulness of these categories.

Part of the nodes table for the data collected from the Variae.

However, a specific problem did arise when trying to enter the geographic location of individuals within the network. When I initially started my project I expected I would able to pinpoint the 'home' location of an individual, in essence where they spend most of their time. However, this rarely came up while reading the Variae and therefore left a column of almost entirely 'unknowns'. For example, I was able to work out that a certain Florianus and Annas were both involved in a dispute over a farm at Mazennes, but the text provided no clue to whether they were actually from this area. A second and more serious problem was that by focusing on the 'home' location of an individual, I was in danger of ignoring what the source was telling me with regards to the geographic mobility of certain people within the Ostrogothic Kingdom, as individuals in the Variae were appearing in multiple places. My dissertation supervisor suggested that a solution to these problems could be to change my initial label of 'location' for the column to a more general one of 'zones of activity'. I believe this solution, of entering multiple locations, helped to avoid losing some of the nuance of the Variae. In one of the most extreme instances, the Praetorian Prefect Faustus, could be found in 14 different locations, ranging from the Cottian Alps to Campania, and instances such as these could not be simply ignored.

Entering the data for the other labels in the nodes table was generally easier, however a number of issues did arise when deciding the ethnicity of a particular person, especially whether they should be termed Roman or Gothic. My main sources for the decision part of this category were two reference works, The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire. and the prosopography found within Amory's People and Identity in Ostrogothic Italy, 489-554. As early medieval scholarship has moved to a more fluid definition of ethnicity, these works had a number of criteria for determining whether a person was Roman or Gothic, aside from the linguistic origin of their name. This, of course, meant there were certain scenarios where the ethnicity of a person was not clear. For example, neither Amory or Martindale could decide the best term to describe an individual called Starcedus. Furthermore, an individual named Colossaeus may have initially appeared to have a Roman name, but the Variae themselves state that he is Gothic (Var. III 23). In some instances there were people who were neither Gothic or Roman, therefore I often used the particular context of an individual to make a decision. For example, Clovis, as King of the Franks, was termed 'Frankish'.

Further complications were the result of my translation of the Variae, the nineteenth-century edition by Thomas Hodgkin. As the best version of the Variae available in English, it is a pivotal work for my dissertation, especially for the purposes of collecting data. This is due to the fact that it contains all the letters from Latin edition, even if in an abridged format. However, it is not perfect, Hodgkin has a tendency to be inconsistent in his use of names and titles. The Assuin mentioned in Book 1, is the same as the Ossuin in Books 3 and 4, however Hodgkin uses both versions of the name without stating it is the same person. In such confusing instances, my reference works were valuable in establishing such connections.

Part of the incidence matrix compiled for the dissertation.

Concurrently to entering the data for the nodes table, I had to compile an incidence matrix to create the wedges or connections within the social network. As shown above, this involved entering a '1' in a column when an individual was a participant in a letter or a '0' if they were not. The letters of the Variae were represented in the top row by the alphabet. A matrix such as this was the easiest way to collect the data, as it accommodated my approach of reading through the Variae one by one. However, it was difficult to transfer this part of the database over to Gephi, the software I am using for the metrics and visualisation of the network. I was therefore required to create a source-target table (as shown below) to do this. This simply involved typing the two IDs (their numerical reference) of the participants within the connection and attributing to them a 'weight'. A higher 'weight' between two people indicates that they are more closely connected, for my purposes this was how often they were mentioned together within Cassiodorus' letters, which was often only once.

Source-Target Table for connections in the network.

Visualisation of my network in Gephi.

The creating of the source-target table formed the final part of my data collection process. After this I transferred it all over to Gephi and ran an algorithm, which helped to create the visualisation of the network also shown above. I immediately detected, unsurprisingly, that Theodoric the Great was at the centre of the network due to his participation in all the letters of the first five books of the Variae. However, I also noticed a number of cliques or groups within the network, particularly around those individuals who were based around Rome or were members of the senate. Argolicus, the Urban Prefect of the city is the most connected individual in the network aside from Theodoric. As my dissertation work continues, I will continue to analyse these different intricacies of the network, most notably by using the metric tools available within Gephi.

Primary Sources:

Cassiodorus, Variae translated in The Letters of Cassiodorus: Being A Condensed Translation Of The Variae Epistolae Of Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator translated by Thomas Hodgkin. London: Henry Frowde, 1886.

Secondary Sources:

Amory, Patrick. People and Identity in Ostrogothic Italy, 489-554. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997

The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, Vol 3 edited by Arnold Jones, John Martindale and John Morris. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Scott, John. Social Network Analysis: A Handbook. 2017 ed. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, 1991.

Thursday, 20 September 2018

Constructing Outer Space?: The Politics of Astronomy in Carolingian Europe

Traditionally, early medieval and Carolingian astronomy has often been dismissed as a period of little or no progress in the history of science. However, over the last several decades a number of scholars have sought to engage with the astronomy of this era on its own terms; viewing it within its own cultural context and and seeking to prove that this still worthy studying. Paul E. Dutton has argued for an understanding of Carolingian astronomy based on the divinatory and historical meanings it sought to find in the stars. Meanwhile, Stephen C. McCluskey has emphasised the textual aspect of Carolingian astronomy and the way it was often based on the elaboration and interpretation of classical treatises, much more than natural observation. The cultural aspect of early medieval astronomy is therefore a theme prominent in the relevant historiography. This post aims to build on these studies by suggesting that the cultural influence on astronomy was not only present, but that it was often manipulated for political purposes. Astronomy in Carolingian Europe was therefore not a single discipline or methodology, but was something that always adapted, often consciously, for different purposes and circumstances. I will show this political use of astronomy by looking at three examples; the illuminated manuscript entitled the Leiden Aratea, the relationship between the Irish scholar Dungal and Charlemagne and finally the passing of Halley's Comet during the reign of Louis the Pious in 837.

However, first it is necessary to outline some of the traditions that influenced Carolingian astronomy, in order to understand the 'cultural repository' from which those gazing at the stars could take from. Mccluskey has done a large amount of work outlining the strands of thought concerning astronomy in early medieval Europe. He argues that traditions regarding astronomy can be put into a number of groups. Firstly, the Roman heritage of astronomy as one of the mathematical disciplines within the seven liberal arts. Next, the tradition of computus- used for determining the date of Easter. These traditions also went alongside the monastic practice of using the stars for timekeeping, in order to determine times for praying, and finally the various astrological techniques used to try and predict future events. This division, as Mccluskey admits, was not always clear cut and in some instances we find in the sources a blend of these different traditions Alongside these instruments used to view the sky, we must also take Dutton's timely reminder that the medieval sky was not as empty as the modern one. In contrast, to the tendency of science today to see outer space as mostly a void between different celestial objects, the sky for medieval observers was full of movement and meaning. It was often also a way through one could try and determine the will of God through signs and omens. With these points in mind we are in a better position to understand the way in which astronomy could be manipulated and the power and influence it could hold.

The Leiden Aratea and the use of the Classical tradition.

Orion the Hunter from the Leiden Aratea

The Leiden Aratea is a ninth century copy of an astronomical and meteorlogical treatise written by the Greek writer Aratus (315-240/39 BCE) and is our first example of the political use of astronomy in Carolingian Europe. However, the Carolingian version does not originate from the original text, a long tradition of copying the treatise existed before the ninth century. The Carolingian version of the Aratea mainly consists of Claudius Caesar Germanicus' first century Latin translation and is supplemented by portions of a second Latin translation by Rufius Festus Avienus in the fourth century. The Leiden Aratea also contains 39 illustrated miniatures depicting the seasons, planets and constellations. These borrow from Classical symbolism with each miniature being a god, hero, object or animal. For example, the image above shows Orion the Hunter overlying the synonymous constellation. The Leiden Aratea was therefore closely not only connected to classical ideas regarding astronomy, but also the textual tradition of copying astronomical treatises.

While this may at first seem innocent enough at first, the Leiden Aratea must be put into the wider context of the Carolingian Renaissance. This term has been has been highly debated, but it can be broadly defined as a revival of intellectual learning during the reign of Charlemagne and the Emperor Louis. Part of this renaissance involved correcting classical texts, such as the Leiden Aratea, that had been passed down. Katzenstein comments that this interest in classical texts was not simply a nostalgia for a past however, but that it was closely tied to an interest at the Carolingian Court to acquire worldly knowledge which would enable Christians to understand theological truths better. This fact can also be seen in the predominant role clerics played during the Carolingian Renaissance. Understandably, all this means that there was also a political benefit to correcting classical texts, as it provided rulers such as Charlemagne with the prestige of supposedly holding greater knowledge of religious truths.

So how does the Leiden Aratea fit into into this wider context? The Leiden Aratea was not a practical text, it would have been hard for anyone to use it to accurately gaze at the stars. Instead, we must connect to the aforementioned tradition Roman astronomy as part of the seven liberal arts. In many of the extant libraries of Carolingian monasteries we find that texts associated with the liberal arts were kept separate to those that focused on other methods of astronomy, such as the much more practical methodology of computus. From this it is clear to see that classical texts such as the Leiden Aratea were not seen to have the same use as other astronomical texts. Instead, the Aratea can be said to have an ideological rather than practical purpose. Texts such as this were often more or less directly copied from their classical counterparts. Even the miniatures in the Leiden Aratea, while adapted to norms of Carolingian illumination, would have likely been derived from preexisting manuscripts. The Aratea was therefore meant to draw a direct connection to the liberal tradition of Roman astronomy. As mentioned above, an education in the classical tradition was one of the key components of the Carolingian Renaissance. The Aratea was therefore one of the individual texts used during the renaissance to try and boost the prestige of the Carolingian Court, showing us the political power that astronomical treatises could hold, especially when drawing from the classical tradition.

The Politics in Dungal's letter to Charlemagne in 811

If the Leiden Aratea shows us how classical astronomical texts could be used for political benefit, Dungal's letter to Charlemagne in 811 can also reveal to us how an individual could use his personal knowledge of the sky for personal gain at he Carolingian Court. However, to understand why may have used his knowledge for political purposes, it is first necessary to provide the relevant context. In 810/811, Charlemagne contacted the Irish scholar, one of many insular intellectuals within the Carolingian Empire, regarding two recent solar eclipses. However, only two extant letters survive from this exchange. While this would suggest that Charlemagne considered Dungal an authority on astronomy, we should not presume this means he was a prominent political figure at the Carolingian Court. The lack of evidence on Dungal in contrast to scholars such as Alcuin means it is difficult to ascertain his level of influence at court. This can be seen by the fact that Dungal was once thought to be four separate people before the unity of his surviving texts was established. In fact, Garrison has argued that Dungal may have been a peripheral figure in the intellectual hierarchy within the Carolingian Empire. A letter to Theodrada, the daughter of Charlemagne, suggests he is barely acquainted with her. Furthermore, a letter to an abbot suggests he was actively seeking patronage and that he did not have the direct support of the court. With this in mind, we can understand that when Charlemagne contacted Dungal regarding the solar eclipses, he was provided with an opportunity to display his astronomical knowledge and ultimately how he could contribute to the intellectual culture at court.

Dungal's letter to Charlemagne in 811 about the two recent solar eclipses shows this political motivation in action. While writing his reply, Dungal heavily quoted from Macrobius' Commentary on the Dream of Scipio, interspersing it with commentary from Pliny. Macrobius' text itself emerges from the fifth century. While mentioning all of this regarding Macrobius and Pliny was necessary to set up his answer to Charlemagne's questions regarding the eclipses, it also provided an opportunity to display the extent of his astronomical and intellectual knowledge. Dungal also in the reply complained about his lack of access to Pliny, therefore highlighting the fact that while he remained on the periphery of Carolingian intellectual life his abilities were being underutilised.

However, this use of astronomical knowledge to gain political favour is best seen when Dungal mentions the most controversial part of Macrobius' Commentary, which tries to resolve a dispute between Plato and Cicero on the placement of the Sun. Plato suggested that the Sun was sixth in the placement of the planets inward from Saturn, whereas Cicero claimed it was fourth inward from Saturn. Dungal's political motivation is seen when he becomes deliberately selective in using Macrobius to present this dispute, for example he omits the latter's support of the Platonic school of thought on the placement of the Sun. This was because the Ciceronian view was more popular at the Carolingian Court. Dungal was therefore deliberately manipulating an astronomical text to further his chances of being accepted into the higher parts of the Carolingian intellectual hierarchy. This of course, on top of his other rhetorical strategies in the letter, shows a concerted effort by Dungal to use his astronomical knowledge for political advantage.

Louis the Pious and the 'Anxiety' of Astronomy

Why did the passing of Halley's Comet cause such an emotional response in Louis and The Astronomer? The passing of Halley's Comet was not the first time in the Vita Hludovici that political or personal fortunes could be associated with celestial objects or omens. Just before a military disaster in the Spanish March in 827, 'there appeared terrible battle lines in the night sky reddened with human blood flashing with the colour of fire'. This of course was seen as a negative sign, however in 828/829, Louis received a certain grain from Gascony that had fallen from the sky. We also find this association between fortunes and space in other sources such as Einhard's biography of Charlemagne, the Vita Karoli Magni. Which describes a number of omens before Charlemagne's death such as 'a certain black spot' which was 'seen on the Sun for a total of seven days'. Paul E. Dutton has aptly described the implications of this constant connecting of cosmological events to fortunes on the political stage, with the sky becoming 'a political and theological hermeneutics'. Astronomy was therefore seen as a system of interpretation and methodology for matters that affected the ruling of the Carolingian Empire. Consequentially, the passing of Halley's Comet in 837, while not a physical threat to Earth, was still a seen as a political threat to Louis and other Carolingian rulers, due to the cultural and political meanings that celestial objects held.

Conclusion

This post has shown that studies on impact of culture on astronomy can be taken a step further, by highlighting the role politics often played in the study of the skies. This took multiple forms, from the production of texts for the purposes of prestige, the personal manipulation of knowledge and the political uncertainty objects in Outer Space could bring. Therefore, this article has highlighted the need to view astronomy not just as an empirical discipline or as a static cultural tradition, but something that is contingent and can be actively utilised in political settings. It is also hoped this post shows the need for further consideration of the politics of astronomy in other contexts, geographically and temporally. Nevertheless, it is still clear that in Carolingian Europe, astronomy played an important political role.

Bibliography

Primary Sources:

The Astronomer, Vita Hludovici in Charlemagne and Louis the Pious: Lives by Einhard, Notker, Ermoldus, Thegan and the Astronomer translated by Thomas F.X. Noble. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2009.

Einhard, Vita Karoli Magni in Charlemagne and Louis the Pious: Lives by Einhard, Notker, Ermoldus, Thegan and the Astronomer translated by Thomas F.X. Noble. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2009.

Secondary Sources:

However, first it is necessary to outline some of the traditions that influenced Carolingian astronomy, in order to understand the 'cultural repository' from which those gazing at the stars could take from. Mccluskey has done a large amount of work outlining the strands of thought concerning astronomy in early medieval Europe. He argues that traditions regarding astronomy can be put into a number of groups. Firstly, the Roman heritage of astronomy as one of the mathematical disciplines within the seven liberal arts. Next, the tradition of computus- used for determining the date of Easter. These traditions also went alongside the monastic practice of using the stars for timekeeping, in order to determine times for praying, and finally the various astrological techniques used to try and predict future events. This division, as Mccluskey admits, was not always clear cut and in some instances we find in the sources a blend of these different traditions Alongside these instruments used to view the sky, we must also take Dutton's timely reminder that the medieval sky was not as empty as the modern one. In contrast, to the tendency of science today to see outer space as mostly a void between different celestial objects, the sky for medieval observers was full of movement and meaning. It was often also a way through one could try and determine the will of God through signs and omens. With these points in mind we are in a better position to understand the way in which astronomy could be manipulated and the power and influence it could hold.

The Leiden Aratea and the use of the Classical tradition.

Orion the Hunter from the Leiden Aratea

The Leiden Aratea is a ninth century copy of an astronomical and meteorlogical treatise written by the Greek writer Aratus (315-240/39 BCE) and is our first example of the political use of astronomy in Carolingian Europe. However, the Carolingian version does not originate from the original text, a long tradition of copying the treatise existed before the ninth century. The Carolingian version of the Aratea mainly consists of Claudius Caesar Germanicus' first century Latin translation and is supplemented by portions of a second Latin translation by Rufius Festus Avienus in the fourth century. The Leiden Aratea also contains 39 illustrated miniatures depicting the seasons, planets and constellations. These borrow from Classical symbolism with each miniature being a god, hero, object or animal. For example, the image above shows Orion the Hunter overlying the synonymous constellation. The Leiden Aratea was therefore closely not only connected to classical ideas regarding astronomy, but also the textual tradition of copying astronomical treatises.

While this may at first seem innocent enough at first, the Leiden Aratea must be put into the wider context of the Carolingian Renaissance. This term has been has been highly debated, but it can be broadly defined as a revival of intellectual learning during the reign of Charlemagne and the Emperor Louis. Part of this renaissance involved correcting classical texts, such as the Leiden Aratea, that had been passed down. Katzenstein comments that this interest in classical texts was not simply a nostalgia for a past however, but that it was closely tied to an interest at the Carolingian Court to acquire worldly knowledge which would enable Christians to understand theological truths better. This fact can also be seen in the predominant role clerics played during the Carolingian Renaissance. Understandably, all this means that there was also a political benefit to correcting classical texts, as it provided rulers such as Charlemagne with the prestige of supposedly holding greater knowledge of religious truths.

So how does the Leiden Aratea fit into into this wider context? The Leiden Aratea was not a practical text, it would have been hard for anyone to use it to accurately gaze at the stars. Instead, we must connect to the aforementioned tradition Roman astronomy as part of the seven liberal arts. In many of the extant libraries of Carolingian monasteries we find that texts associated with the liberal arts were kept separate to those that focused on other methods of astronomy, such as the much more practical methodology of computus. From this it is clear to see that classical texts such as the Leiden Aratea were not seen to have the same use as other astronomical texts. Instead, the Aratea can be said to have an ideological rather than practical purpose. Texts such as this were often more or less directly copied from their classical counterparts. Even the miniatures in the Leiden Aratea, while adapted to norms of Carolingian illumination, would have likely been derived from preexisting manuscripts. The Aratea was therefore meant to draw a direct connection to the liberal tradition of Roman astronomy. As mentioned above, an education in the classical tradition was one of the key components of the Carolingian Renaissance. The Aratea was therefore one of the individual texts used during the renaissance to try and boost the prestige of the Carolingian Court, showing us the political power that astronomical treatises could hold, especially when drawing from the classical tradition.

The Politics in Dungal's letter to Charlemagne in 811

If the Leiden Aratea shows us how classical astronomical texts could be used for political benefit, Dungal's letter to Charlemagne in 811 can also reveal to us how an individual could use his personal knowledge of the sky for personal gain at he Carolingian Court. However, to understand why may have used his knowledge for political purposes, it is first necessary to provide the relevant context. In 810/811, Charlemagne contacted the Irish scholar, one of many insular intellectuals within the Carolingian Empire, regarding two recent solar eclipses. However, only two extant letters survive from this exchange. While this would suggest that Charlemagne considered Dungal an authority on astronomy, we should not presume this means he was a prominent political figure at the Carolingian Court. The lack of evidence on Dungal in contrast to scholars such as Alcuin means it is difficult to ascertain his level of influence at court. This can be seen by the fact that Dungal was once thought to be four separate people before the unity of his surviving texts was established. In fact, Garrison has argued that Dungal may have been a peripheral figure in the intellectual hierarchy within the Carolingian Empire. A letter to Theodrada, the daughter of Charlemagne, suggests he is barely acquainted with her. Furthermore, a letter to an abbot suggests he was actively seeking patronage and that he did not have the direct support of the court. With this in mind, we can understand that when Charlemagne contacted Dungal regarding the solar eclipses, he was provided with an opportunity to display his astronomical knowledge and ultimately how he could contribute to the intellectual culture at court.

Dungal's letter to Charlemagne in 811 about the two recent solar eclipses shows this political motivation in action. While writing his reply, Dungal heavily quoted from Macrobius' Commentary on the Dream of Scipio, interspersing it with commentary from Pliny. Macrobius' text itself emerges from the fifth century. While mentioning all of this regarding Macrobius and Pliny was necessary to set up his answer to Charlemagne's questions regarding the eclipses, it also provided an opportunity to display the extent of his astronomical and intellectual knowledge. Dungal also in the reply complained about his lack of access to Pliny, therefore highlighting the fact that while he remained on the periphery of Carolingian intellectual life his abilities were being underutilised.

However, this use of astronomical knowledge to gain political favour is best seen when Dungal mentions the most controversial part of Macrobius' Commentary, which tries to resolve a dispute between Plato and Cicero on the placement of the Sun. Plato suggested that the Sun was sixth in the placement of the planets inward from Saturn, whereas Cicero claimed it was fourth inward from Saturn. Dungal's political motivation is seen when he becomes deliberately selective in using Macrobius to present this dispute, for example he omits the latter's support of the Platonic school of thought on the placement of the Sun. This was because the Ciceronian view was more popular at the Carolingian Court. Dungal was therefore deliberately manipulating an astronomical text to further his chances of being accepted into the higher parts of the Carolingian intellectual hierarchy. This of course, on top of his other rhetorical strategies in the letter, shows a concerted effort by Dungal to use his astronomical knowledge for political advantage.

Louis the Pious and the 'Anxiety' of Astronomy

The Passing of Halley's Comet in 1986

The previous two examples, the Leiden Aratea and Dungal's letter to Charlemagne in 811, show the power astronomy could hold as a political or symbolic device. As these both relied on knowledge and texts within their control, they were effective devices to achieve their political aims. However, the passing of Halley's Comet in 837 shows us a different example where the political significance attached to astronomy could sometimes be more problematic than helpful. This of course being especially true in this instance as celestial objects such as comets are for the time being ultimately out of human control. Halley's Comet passed within 3 million miles of Earth in 837 in contrast to 1986 when it was 24 million years away, it would therefore have likely been a prominent object in the Carolingian sky at the time of its passing. As such, the comet is mentioned in numerous Carolingian sources, such as the Annals of Fulda and in the writings of Lupus of Ferrières. However, the most prominent account comes in a biography of the Emperor Louis written by a figure referred to as 'The Astronomer'. This biography, the Vita Hludovici, can reveal to us how astronomy could often become problematic for Carolingian rulers.

This is best illustrated by the emotional response The Astronomer and the Emperor Louis have to the passing of the comet.The passage describing its appearance starts with 'In the middle of the Easter celebration, a dire and sad portent, a comet, appeared in the sign of Virgo'. Immediately, The Astronomer suggests that the sight of the comet may be a bad omen for things to come. However, the intensity of the passage picks up 'when he [Louis] saw that the comet had stopped, was anxious, before he went to bed, to interrogate a certain person who had been summoned, namely me [The Astronomer]'. Upon appearance of the comet, Louis knows the impact it could have on him and his kingdom, he immediately summons the Astronomer to try and find some reassurance. This suggests that celestial entities, such as Halley's Comet, could provoke a feeling of ensuing danger. The Astronomer later reminds Louis 'to not fear the sign from heaven which the nations fear', quoting Jeremiah 10:2. The original scriptural passage can be found in the context of God talking to the Israelites, therefore the Astronomer is reminding Louis, as ruler of the Carolingian Empire, to not fear celestial objects like other 'nations' do. This shows how fears of political change could often be linked to what appeared in the sky, as the Franks standing in for the Israelites, are not supposed to hold this fear, as a result of being God's chosen people.

Louis immediately affirms this and suggests that he and The Astronomer should actually be grateful for God giving them a forewarning of trouble. Louis still however seems anxious as 'Having said this, he indulged in a little wine' and 'kept vigil all night', as the morning approached 'he ordered alms'. These responses suggest that Louis is still not fully convinced that the comet is not a threat, for example by the religious actions he is trying to placate God. Once all this is all over, it is revealed that the comet was not a threat and in fact a 'hunt yielded to him vastly more than usual', suggesting that it was in fact a positive omen, Halley's Comet, as a physical object outside of Louis's control, was therefore a great source of anxiety and uncertainty as what it meant for him or the Carolingian Empire. It would do well to mention here that Scott Ashley has recently suggested that it was not Halley's Comet that Louis and The Astronomer were talking about, but that the object in space was instead a nova or an appearance of Mercury. While this cannot completely be confirmed or denied, it still does take away from the reaction Louis and The Astronomer had to the object.

Conclusion