Over the summer and since my previous post, I have completed entering the data necessary to create a social network based on Cassiodorus' Variae. In this entry, I not only hope to show the process by which this was carried out, but also show the problems that can arise in a research project of this size and nature and how they can be resolved or at least circumvented. I will do this by firstly examining the process for collecting the data for the nodes or individuals within the network and then move on to look at the wedges or connections.

The data for this project was collected through a reading of the first five books of Cassiodorus' Variae and then was entered into Microsoft Excel. The first Excel sheet for my database was for the 'nodes'. This mainly consisted of the characteristics of the individuals in the network which were collected under a series of labels; their name, the origin of their name or ethnicity, gender, occupation and finally their location. An additional column was reserved for a range of additional notes relevant to creating the network, such as my reasoning for making certain decisions. It is clear that the labels I used for collecting the data were based on structures (such as class and ethnicity) that have had prominence in recent debates on Ostrogothic Italy. While this may indeed have neglected other aspects of the text, I believe my choices are justified as one of the aims of my project was to ask whether recent historiography stands up to scrutiny when the Variae are analysed quantitatively instead of qualitatively. Likewise, I believe a technique like Social Network Analysis, as it examines connections between people, can be used to examine the usefulness of these categories.

However, a specific problem did arise when trying to enter the geographic location of individuals within the network. When I initially started my project I expected I would able to pinpoint the 'home' location of an individual, in essence where they spend most of their time. However, this rarely came up while reading the Variae and therefore left a column of almost entirely 'unknowns'. For example, I was able to work out that a certain Florianus and Annas were both involved in a dispute over a farm at Mazennes, but the text provided no clue to whether they were actually from this area. A second and more serious problem was that by focusing on the 'home' location of an individual, I was in danger of ignoring what the source was telling me with regards to the geographic mobility of certain people within the Ostrogothic Kingdom, as individuals in the Variae were appearing in multiple places. My dissertation supervisor suggested that a solution to these problems could be to change my initial label of 'location' for the column to a more general one of 'zones of activity'. I believe this solution, of entering multiple locations, helped to avoid losing some of the nuance of the Variae. In one of the most extreme instances, the Praetorian Prefect Faustus, could be found in 14 different locations, ranging from the Cottian Alps to Campania, and instances such as these could not be simply ignored.

Entering the data for the other labels in the nodes table was generally easier, however a number of issues did arise when deciding the ethnicity of a particular person, especially whether they should be termed Roman or Gothic. My main sources for the decision part of this category were two reference works, The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire. and the prosopography found within Amory's People and Identity in Ostrogothic Italy, 489-554. As early medieval scholarship has moved to a more fluid definition of ethnicity, these works had a number of criteria for determining whether a person was Roman or Gothic, aside from the linguistic origin of their name. This, of course, meant there were certain scenarios where the ethnicity of a person was not clear. For example, neither Amory or Martindale could decide the best term to describe an individual called Starcedus. Furthermore, an individual named Colossaeus may have initially appeared to have a Roman name, but the Variae themselves state that he is Gothic (Var. III 23). In some instances there were people who were neither Gothic or Roman, therefore I often used the particular context of an individual to make a decision. For example, Clovis, as King of the Franks, was termed 'Frankish'.

Further complications were the result of my translation of the Variae, the nineteenth-century edition by Thomas Hodgkin. As the best version of the Variae available in English, it is a pivotal work for my dissertation, especially for the purposes of collecting data. This is due to the fact that it contains all the letters from Latin edition, even if in an abridged format. However, it is not perfect, Hodgkin has a tendency to be inconsistent in his use of names and titles. The Assuin mentioned in Book 1, is the same as the Ossuin in Books 3 and 4, however Hodgkin uses both versions of the name without stating it is the same person. In such confusing instances, my reference works were valuable in establishing such connections.

Concurrently to entering the data for the nodes table, I had to compile an incidence matrix to create the wedges or connections within the social network. As shown above, this involved entering a '1' in a column when an individual was a participant in a letter or a '0' if they were not. The letters of the Variae were represented in the top row by the alphabet. A matrix such as this was the easiest way to collect the data, as it accommodated my approach of reading through the Variae one by one. However, it was difficult to transfer this part of the database over to Gephi, the software I am using for the metrics and visualisation of the network. I was therefore required to create a source-target table (as shown below) to do this. This simply involved typing the two IDs (their numerical reference) of the participants within the connection and attributing to them a 'weight'. A higher 'weight' between two people indicates that they are more closely connected, for my purposes this was how often they were mentioned together within Cassiodorus' letters, which was often only once.

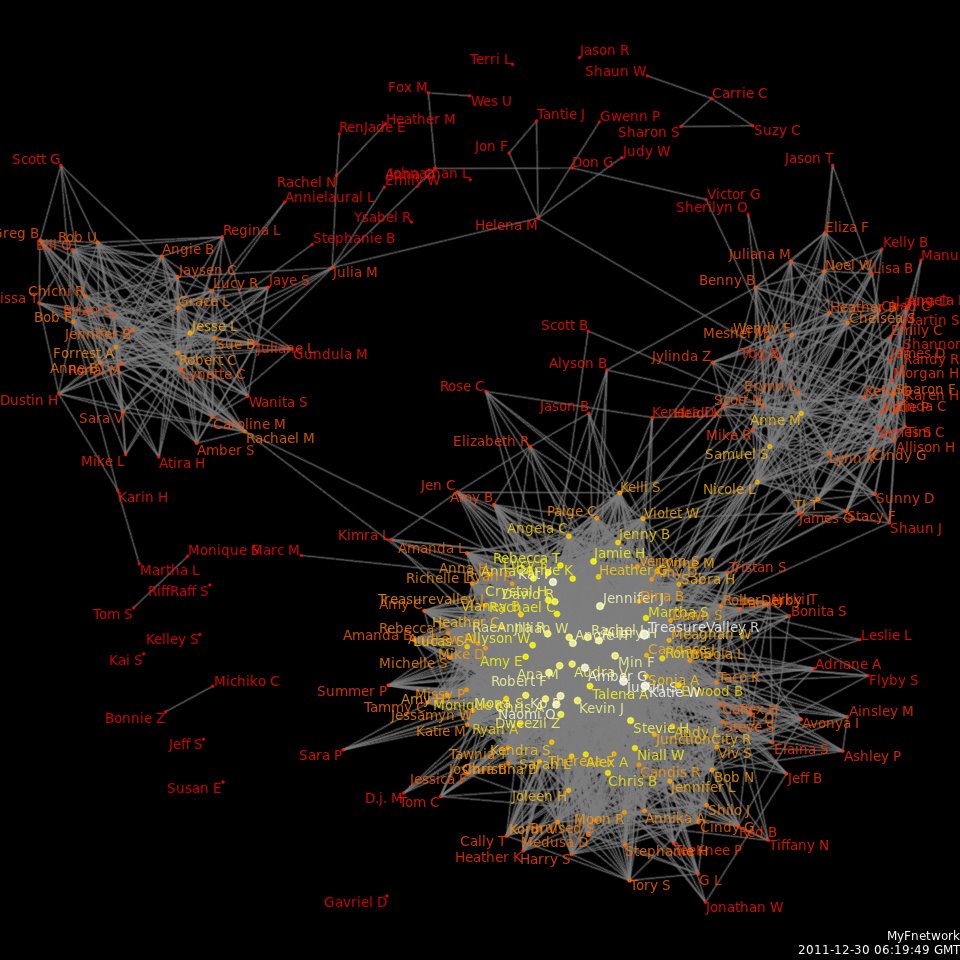

Visualisation of my network in Gephi.

The creating of the source-target table formed the final part of my data collection process. After this I transferred it all over to Gephi and ran an algorithm, which helped to create the visualisation of the network also shown above. I immediately detected, unsurprisingly, that Theodoric the Great was at the centre of the network due to his participation in all the letters of the first five books of the Variae. However, I also noticed a number of cliques or groups within the network, particularly around those individuals who were based around Rome or were members of the senate. Argolicus, the Urban Prefect of the city is the most connected individual in the network aside from Theodoric. As my dissertation work continues, I will continue to analyse these different intricacies of the network, most notably by using the metric tools available within Gephi.

Primary Sources:

The data for this project was collected through a reading of the first five books of Cassiodorus' Variae and then was entered into Microsoft Excel. The first Excel sheet for my database was for the 'nodes'. This mainly consisted of the characteristics of the individuals in the network which were collected under a series of labels; their name, the origin of their name or ethnicity, gender, occupation and finally their location. An additional column was reserved for a range of additional notes relevant to creating the network, such as my reasoning for making certain decisions. It is clear that the labels I used for collecting the data were based on structures (such as class and ethnicity) that have had prominence in recent debates on Ostrogothic Italy. While this may indeed have neglected other aspects of the text, I believe my choices are justified as one of the aims of my project was to ask whether recent historiography stands up to scrutiny when the Variae are analysed quantitatively instead of qualitatively. Likewise, I believe a technique like Social Network Analysis, as it examines connections between people, can be used to examine the usefulness of these categories.

Part of the nodes table for the data collected from the Variae.

However, a specific problem did arise when trying to enter the geographic location of individuals within the network. When I initially started my project I expected I would able to pinpoint the 'home' location of an individual, in essence where they spend most of their time. However, this rarely came up while reading the Variae and therefore left a column of almost entirely 'unknowns'. For example, I was able to work out that a certain Florianus and Annas were both involved in a dispute over a farm at Mazennes, but the text provided no clue to whether they were actually from this area. A second and more serious problem was that by focusing on the 'home' location of an individual, I was in danger of ignoring what the source was telling me with regards to the geographic mobility of certain people within the Ostrogothic Kingdom, as individuals in the Variae were appearing in multiple places. My dissertation supervisor suggested that a solution to these problems could be to change my initial label of 'location' for the column to a more general one of 'zones of activity'. I believe this solution, of entering multiple locations, helped to avoid losing some of the nuance of the Variae. In one of the most extreme instances, the Praetorian Prefect Faustus, could be found in 14 different locations, ranging from the Cottian Alps to Campania, and instances such as these could not be simply ignored.

Entering the data for the other labels in the nodes table was generally easier, however a number of issues did arise when deciding the ethnicity of a particular person, especially whether they should be termed Roman or Gothic. My main sources for the decision part of this category were two reference works, The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire. and the prosopography found within Amory's People and Identity in Ostrogothic Italy, 489-554. As early medieval scholarship has moved to a more fluid definition of ethnicity, these works had a number of criteria for determining whether a person was Roman or Gothic, aside from the linguistic origin of their name. This, of course, meant there were certain scenarios where the ethnicity of a person was not clear. For example, neither Amory or Martindale could decide the best term to describe an individual called Starcedus. Furthermore, an individual named Colossaeus may have initially appeared to have a Roman name, but the Variae themselves state that he is Gothic (Var. III 23). In some instances there were people who were neither Gothic or Roman, therefore I often used the particular context of an individual to make a decision. For example, Clovis, as King of the Franks, was termed 'Frankish'.

Further complications were the result of my translation of the Variae, the nineteenth-century edition by Thomas Hodgkin. As the best version of the Variae available in English, it is a pivotal work for my dissertation, especially for the purposes of collecting data. This is due to the fact that it contains all the letters from Latin edition, even if in an abridged format. However, it is not perfect, Hodgkin has a tendency to be inconsistent in his use of names and titles. The Assuin mentioned in Book 1, is the same as the Ossuin in Books 3 and 4, however Hodgkin uses both versions of the name without stating it is the same person. In such confusing instances, my reference works were valuable in establishing such connections.

Part of the incidence matrix compiled for the dissertation.

Concurrently to entering the data for the nodes table, I had to compile an incidence matrix to create the wedges or connections within the social network. As shown above, this involved entering a '1' in a column when an individual was a participant in a letter or a '0' if they were not. The letters of the Variae were represented in the top row by the alphabet. A matrix such as this was the easiest way to collect the data, as it accommodated my approach of reading through the Variae one by one. However, it was difficult to transfer this part of the database over to Gephi, the software I am using for the metrics and visualisation of the network. I was therefore required to create a source-target table (as shown below) to do this. This simply involved typing the two IDs (their numerical reference) of the participants within the connection and attributing to them a 'weight'. A higher 'weight' between two people indicates that they are more closely connected, for my purposes this was how often they were mentioned together within Cassiodorus' letters, which was often only once.

Source-Target Table for connections in the network.

Visualisation of my network in Gephi.

The creating of the source-target table formed the final part of my data collection process. After this I transferred it all over to Gephi and ran an algorithm, which helped to create the visualisation of the network also shown above. I immediately detected, unsurprisingly, that Theodoric the Great was at the centre of the network due to his participation in all the letters of the first five books of the Variae. However, I also noticed a number of cliques or groups within the network, particularly around those individuals who were based around Rome or were members of the senate. Argolicus, the Urban Prefect of the city is the most connected individual in the network aside from Theodoric. As my dissertation work continues, I will continue to analyse these different intricacies of the network, most notably by using the metric tools available within Gephi.

Primary Sources:

Cassiodorus, Variae translated in The Letters of Cassiodorus: Being A Condensed Translation Of The Variae Epistolae Of Magnus Aurelius Cassiodorus Senator translated by Thomas Hodgkin. London: Henry Frowde, 1886.

Secondary Sources:

Amory, Patrick. People and Identity in Ostrogothic Italy, 489-554. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997

The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, Vol 3 edited by Arnold Jones, John Martindale and John Morris. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Scott, John. Social Network Analysis: A Handbook. 2017 ed. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, 1991.

.jpg/800px-Gesta_Theodorici_-_Flavius_Magnus_Aurelius_Cassiodorus_(c_485_-_c_580).jpg)

.png)